Editor’s note: When discussing evangelism, disciple-making, and church planting, the challenge of the prosperity gospel often looms large in the background, especially in the Global South. To that end, this piece examines the prosperity gospel through the lens of Job in the Old Testament.

“Snake-bit.”

It’s a phrase used in west Texas. “Be careful in that wood pile! You don’t want to get snake-bit!” Rattlesnake bites are not frequent, but they happen often enough that anti-venom is kept on-hand at even the smallest hospitals. Without it, the consequence can be gruesome.

In some respects, the first three chapters of Genesis comprise a story of creation getting “snake-bit.” God, in his grace, immediately applied the anti-venom—an animal sacrificed on behalf of the trespassers—and promised One who would ultimately crush the head of the snake and reverse his toxic effects.

In the early days of US expansion, Chinese railroad workers used snake oil to effectively battle inflammation in their tired joints. Soon fraudulent doctors were creating their own snake oil with local rattlesnakes. The properties in these concoctions did not have the same effect, but the hucksters kept selling it and the people kept buying it.

Today, people who promote the prosperity gospel are offering snake oil to repair the damage done to a snake-bit creation. The solutions they offer are not only ineffective but can severely hamper the true cure found in the one who was high and lifted up (Num. 21:8; John 3:14). The book of Job is an effective antidote to this pervasive problem.

1. The book of Job affirms the possibility of the innocent sufferer (Job 1:1, 8).

From the outset the author offered an almost poetic summary of Job’s spiritual condition: “[Job] was a man of complete integrity, who feared God and turned away from evil” (1:1). Job was not sinless, but the brutal treatment he experienced was not tied to any particular sin.

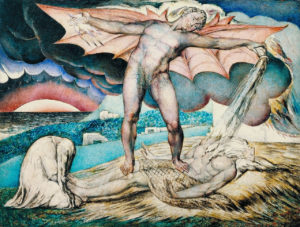

Satan Smiting Job with Boils—William Blake 1826

God dangled Job out there in front of Satan like a piece of raw steak in chapter one. A deal was struck between God and Satan, Job’s entire world was savagely devoured, and yet his faith remained. In chapter two the process began anew and God himself described Job in the same way: “a man of perfect integrity, who fears God and turns away from evil” (2:3). God won the bet, and Satan was not heard from again.

These two chapters of the book of Job are important because they repeatedly tell the reader that Job is an innocent sufferer and so serves as a model of Christ. Job—declared innocent by God—was allowed to suffer as a part of God’s eternal plan. Christ in every sense was and us innocent before God. He suffered as part of God’s eternal plan. This is important because without innocent suffering, substitutionary atonement in Christ could never have occurred and we’d be lost in our sin.

2. The book of Job diagnoses a common belief of the prosperity gospel: God blesses those who are good and curses those who are bad (Job 4:7).

The story should have ended there, but it didn’t. Job’s suffering continues. Four of Job’s friends arrived to help him process his misery. Job 4:7 was a summation of three of the four friends’ position:

“Consider: Who has perished when he was innocent?

Where have the honest been destroyed?”

This statement represented a theological formula that is inherent in the prosperity gospel today: good people are blessed and bad people are cursed. Good people perform the right ceremonies, speak the right phrases, and sow the right things. Bad people cross God with their lack of faith or lack of moral or spiritual achievement. Performance is the difference between suffering and blessing.

Job’s misery is divided into two segments in the Scriptures. In chapters one and two, Job was put to the test by God through God’s wager with Satan, and the reasons for this suffering were independent of and unknown to Job. Yet in the face of horrific loss, Job declared: “The Lord gives, and the Lord takes away. / Blessed be the name of the Lord” (1:21), and “Should we accept only good from God and not adversity?” (2:10)?

Then, in chapters 3–42, Job’s ongoing sufferings had a connection with Job’s attitude. Here, Job’s open declarations that God was unjust (9:22–24) and cruel (7:20) displayed no confidence in God’s sacrificial system. His suffering revealed a heart filled with arrogance and pride. That’s where Elihu entered the story.

3. The book of Job anticipates a comprehensive answer to the problem of all suffering—the heavenly mediator (Job 33:23–30).

As Elihu reflected on the troubles of Job, he wondered what it would be like to have someone from heaven come and serve not only as a middle man between God and Job, but as a ransom (33:24). Once that ransom was paid, people could come to God and pray without worry of rejection or fear of God’s wrath. Instead, they would see God and be glad.

Elihu understood that eventually all suffering is tied to all sin, either directly or indirectly. Therefore to eradicate injustice and sickness and poverty completely, the root of those things must be comprehensively addressed by God himself.

4. The book of Job shows how the prosperity gospel misrepresents God (Job 42:7).

At the end of the book, when God affirms Job, it’s a bit of a shock to the reader. What made Job different from the three friends? With all of his emotional turmoil, Job believed in God’s grace.

God turned to Job’s friends. They never considered that they could be wrong and Job could be right. They believed God’s favor could be bought with good deeds, which diminished his sovereignty by reducing God to a god—from one who is to be worshipped to one who is to be used. They made God contingent on the actions of man. In this way they wrongly represented God.

Snake Charmed

There’s something in all of us that innately draws us to the prosperity gospel. Satan poisons our souls with the prospect of earning God’s favor or condemning us with our failure. The only hope to combat this is the message of grace that can be seen through the story of Job.

Andrew Bristol received his BA from Hardin-Simmons University and his MDiv and DMin from Southwestern Baptist Theological Seminary. He has been serving in Central Asia since 2003. He and his wife have four children and one grandchild.