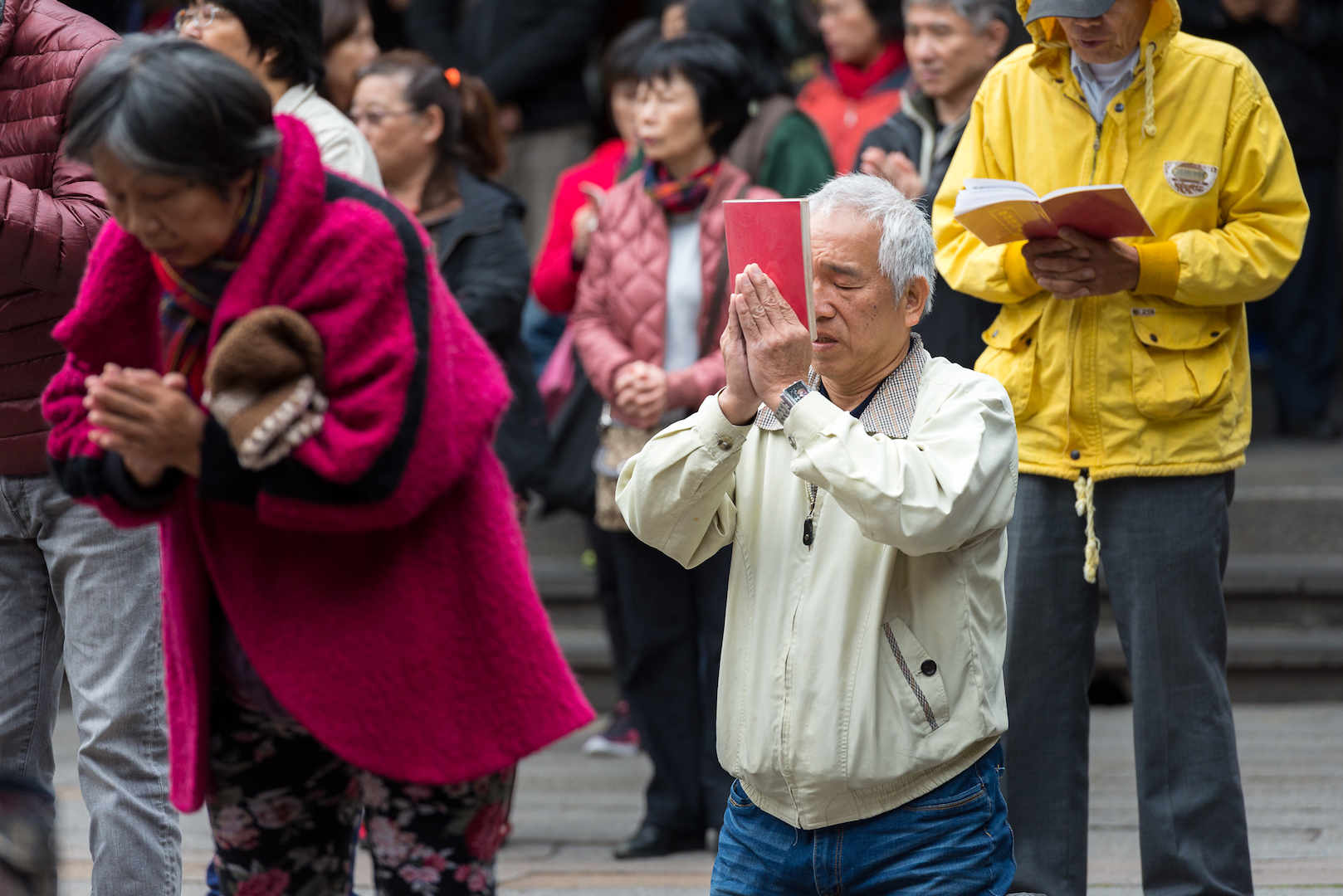

Ministry within honor-shame cultures is a widely discussed topic today. The majority world and especially the East, as we’ve come to realize, doesn’t think the way we do. In a sense, they work on a completely different operating system, which means Western missionaries must adapt their default language and coding when presenting the gospel.

Cultural awareness is the first step, though complete cultural adaptation doesn’t follow as the necessary goal. This is the case in any context, Western or otherwise. When anyone attempts to contextualize the gospel message to a given culture there are inevitable perils. So while great strides have been made in our evangelism as it relates to honor-shame contexts, the proverbial pendulum can swing too far.

What follows are five dangers I see for those seeking to minister in honor-shame contexts. Recognizing them will hopefully protect us from unhelpful overcorrection.

1. Disconnect Honor from Obedience

Western bias no doubt affects our reading of Scripture. You may have noticed this in a common interpretation of Romans 3:23. Some may speak of our missing the mark, or coming up short, of perfectly obeying God’s law. But that’s not exactly what Paul says. Rather, he equates sin with imperfectly and incompletely glorifying God.

Dig up the dirty roots of human sinfulness and death, and you find dishonor. Adam and Eve didn’t honor God, nor were they thankful, so they disobeyed his word. This is the pattern of all sinfulness (Rom. 1:21). Most fundamentally, the human problem is one of failing to glorify God as we ought and as he deserves.

But the biblical witness doesn’t end there. John succinctly defines sin as lawlessness (1 John 3:4). Rather than contradicting Paul, this actually helps us see the link between honor and obedience (see Rom. 1). When Adam failed to honor God, he transgressed the law.

We dishonor by disobeying. So Jesus can say, “If you love me, keep my commandments” (John 14:15). Or Paul can restate the fifth commandment to honor father and mother by writing, “Obey your parents” (Eph 6:1).

2. Ignore the Biblical (Eastern) Roots of Law and Guilt

A missionary once related to me that law is primarily a Western concept, unique in history to certain cultures. But the Bible makes clear that commandments and guilt are as old as humanity. Furthermore, the Law of Moses is an ancient Near Eastern document—and far more than a mere artifact of Jewish culture. It’s the very Word of God.

We should recognize, then, that God has always related to his covenant people through promises and commands. In Adam, as in Christ, God has chosen to relate to all humanity through headship and imputation. Guilt and innocence are therefore universal, biblical concepts.

What’s more, Paul suggests that the whole world is condemned by the law (Rom. 3:19), even if that law is their own conscience bearing witness against them (Rom. 2:14–16).

“If people don’t have a sense of guilt or shame before the righteous requirement of the law, that isn’t the byproduct of an impartial worldview but an active rejection of God’s standards.”

If people don’t have a sense of guilt or shame before the righteous requirement of the law, that isn’t the byproduct of an impartial worldview, but active rejection of God’s standards. It’s a running from revelation, natural or special.

So if we as evangelists avoid talking about law and guilt, then we abandon one of God’s appointed means for revealing our need for Christ.

3. Make the Mistake You Wish to Correct

Just as the West has been blind in many ways to the significance of honor and shame in the biblical witness, we can make a similarly egregious error in Eastern cultures if we ignore concepts of law and guilt. In other words, missionaries are in danger of making the very mistake they wish to correct.

Granted, Western Christians need to wake up to their own proclivities to materialism and consumerism. They need to come face to face with the deeply biblical reality of shame and social exclusion. They need to see, for instance, that the hellishness of eternal punishment is separation from the presence of God. They need to see interdependence and familial love in the church rather than individualism or pure intellectualism. In fact, we could say those counter-cultural lessons are not tertiary but central.

But if so, the same reality must be true for our brothers and sisters in honor-shame contexts. If their home cultures are blind to certain aspects of biblical revelation-especially those as fundamental as law and righteousness and guilt and imputation-then the solution must not be to avoid such concepts.

4. Allow Culture to Be Normative, Not the Bible

Behind all of this is the ancient problem of syncretism, when Christianity doesn’t transform the community but simply conforms to existing patterns or structures. In syncretism, Christianity is added onto prevailing religious and cultural organisms like a grafted branch. It may flourish—and often does—but the guiding principle remains in the existent cultural vine.

In anthropology, we can speak of cultural norms. Such nomenclature reveals something about the nature of culture: it becomes a law (norm) unto itself. It sets the standards. It produces values and mores. It demands appropriate behavior. It even norms our own perceptions and emotions.

“We should, like Jesus and Paul, look for natural bridges to our audience. We should speak a language they understand.”

But that is the role of God’s Word for the Christian community. When we read the Bible, we may tend to look for parts that relate to us and that are translatable into our culture. But God’s Word was never meant to be used so simply. In the church, Christ should be the ruling norm, and he rules his church through Scripture properly handled and rightly interpreted.

5. Misrepresent Biblical Discipleship

Put another way, the Bible doesn’t merely provide us with a variety of discourse alternatives for communicating in disparate contexts. Instead, the Bible supplies a comprehensive analysis of humanity from God’s perspective. He tells us what we should think of ourselves and our cultures. Which means guilt-innocence paradigms—I have especially in mind the weighty theological categories of propitiation, justification, imputation, and sanctification—have a place in our discipleship.

That said, I do believe it’s helpful to contextualize the gospel in evangelism. We should, like Jesus and Paul, look for natural bridges to our audience. We should speak a language they understand. We should meet them on their own turf. We should be clear about the gospel by drawing on cultural sensitivities or even felt needs, whether that is uncleanness or powerlessness or darkness or shame. The gospel speaks to all of these, particularly through our union with Christ.

But that doesn’t mean we should co-op the whole of Christian discipleship into the values of a given culture. We must never downplay the law of Christ or the centrality of obedience as his disciple. If a host culture diminishes disobedience or lacks categories for transgression, the solution isn’t to sidestep the issue. Instead, we must teach believers that to honor the Master means to follow in his steps.

Elliot Clark (MDiv, The Southern Baptist Theological Seminary) lived in Central Asia where he served as a cross-cultural church planter along with his wife and children. He is currently working to train local church leaders overseas with Training Leaders International.