After millennia of being ruled by others, and after the horrific losses of the Holocaust, Jews the world over visit Israel to connect with their roots and behold what, against all odds, now exists as a Jewish homeland. Not every Jew has chosen to claim their legal right to immigrate to Israel, but they still feel connected in Israel to the founders of their faith and ethnicity. Their promised land is more than a collection of holy sites. It is holy in itself.

The Temple Mount

Every year at Passover Seder dinner, as Jews say to one another “Next year in Jerusalem,” they speak with hope of what’s to come. As they wait for God to reestablish an earthly kingdom for them, they journey to what they consider holy, significant places where God has historically made his dwelling among them. Jerusalem hosts two of the most important sites: the Temple and its Western Wall (“the Kotel,” in Hebrew).

The Temple’s central role traces back to the Old Testament as it housed the sacrificial system by which Jews kept the laws of the Torah and the covenant. Priests and scholars served God and instructed the community in the Temple, a place paramount to their identity as Jehovah’s people.

The Temple and the mount on which it was placed has significance that reaches back to the moment when history began. In the Jewish worldview, the Temple Mount was the site of the Garden of Eden. Melchizedek, the king of Salem—which Jews suppose to be Jerusalem—worshiped the Most High God there and blessed Abram. Abraham bound his son Isaac on the Mount, David defended and built a kingdom around it, and Solomon further anchored it in history by erecting on it the Temple of God.

Psalm 137:4 contains the Jews’ distraught cries after they lost the promised land in the exile: “How can we sing the songs of the Lord while in a foreign land?” (NIV). Losing access to the Temple and its eventual destruction created a total disorientation. Without the Temple, the literal question arose: how were they to keep their faith?

Jews believe the Temple Mount—the elevated, open space above the Western Wall—may be the location of the Holy of Holies where God’s presence dwells. Photo by Rob Bye

Today, the spacious, raised Mount of the destroyed Temple is home to two of Islam’s most sacred mosques, Al-Aqsa and the Dome of the Rock. The entire Mount is under Arab authority. Still, Jews believe the Temple Mount to be their holiest site of all. So holy, in fact, that Israel’s chief rabbinate posted a sign above the entrance discouraging Jews from even entering the site lest they stumble unprotected onto what once was the Holy of Holies. It is said that God’s presence is still there.

Today, touching the ancient stones on the Mount connects Jews to David, Abraham, and most importantly, to the presence of God on earth. The Mount is where their prayers rise up to God. Rabbis, in the centuries since the destruction of the second temple, established a system of prescribed prayers, good deeds, and repentance to replace the sacrificial system in Judaism. Since Jews no longer offer sacrifices, their prayers at special places like the Mount are all the more significant because they are expected to carry the weight once borne by sacrificed animals.

The Western Wall

Since it is within current political boundaries, the Temple Mount is inaccessible to most Jews. They feel especially connected to the Kotel as the only portion of the Temple they can touch. Tour guides often explain that though the English term “Wailing Wall” was used during the British Mandate, since the Six Day War in 1967 people have returned to using its traditional Jewish name, the Kotel, literally meaning “the wall” in ancient Hebrew. We in the West sometimes hear it referred to as the Western Wall.

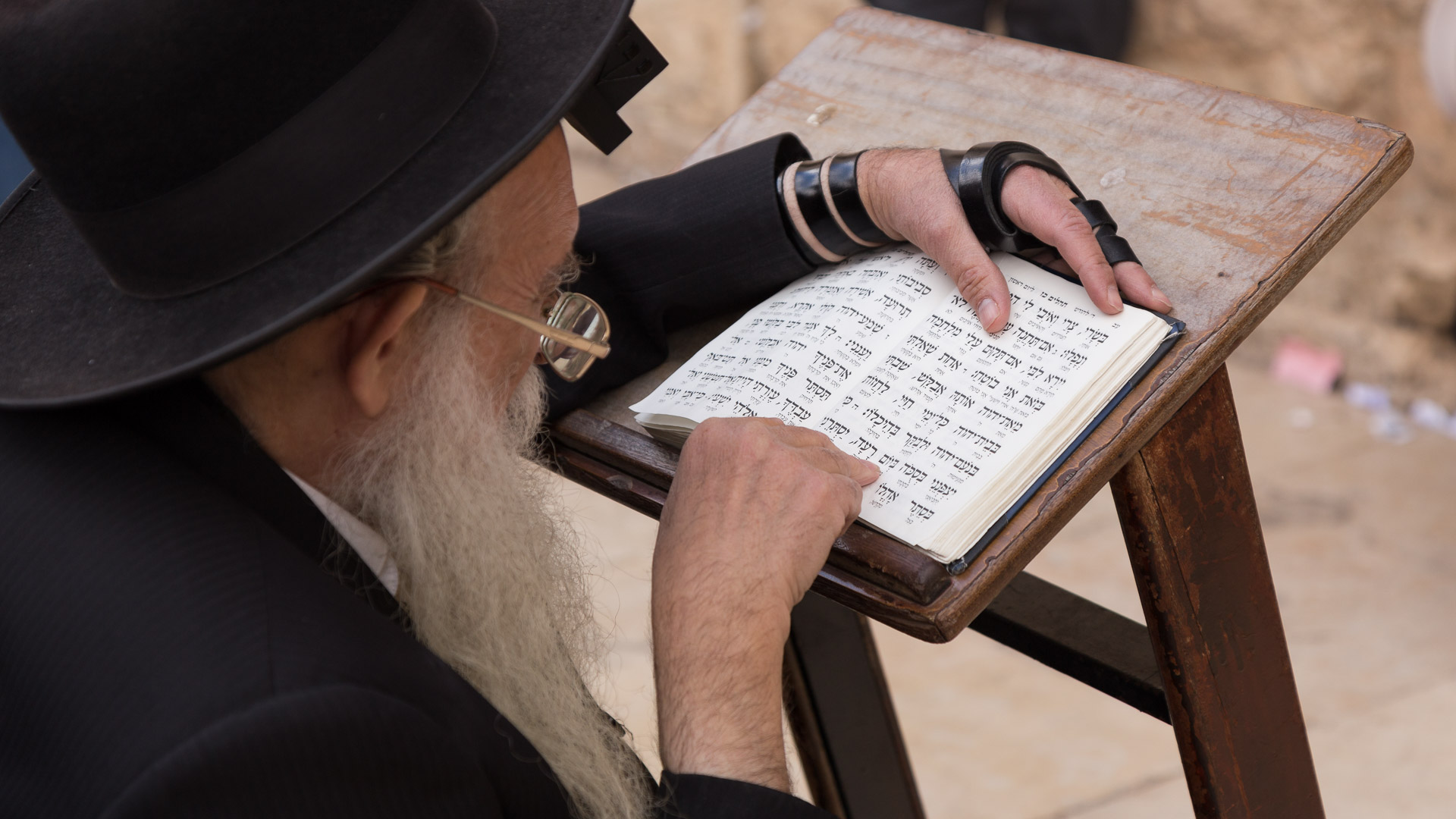

Many Jews feel the closest to God at the Kotel. After a security check and a ritual handwashing at the fountains, men proceed to the Wall via the left side of a partition and women to the right. Men adorn kippot, prayer shawls, and small, black boxes with portions of the Torah inside as they rock back and forth, bow, and cry out with earnest prayers. Women in prayer cover their heads, and some sit in chairs for hours reading from prayer books.

An elderly Orthodox Jew wears tefillin as he reads the Torah in front of the Western Wall in the Old City of Jerusalem. Photo by Max Power

Some people write out prayers, roll them up, and stick them in the crevices between the stones in faith that God will answer. After prayers at the Wall, people walk backward, in respect to God, up the pathway back toward the partition’s edge.

His Kingdom Is Not of This World

As Christians, we have the chance to seek out spiritually hungry Jews for whom Jerusalem is significant and holy. Whether you are in Israel for a tour or you have Jewish friends and colleagues, you can be still, ask God who to talk to, and then approach, ask questions, and listen. Seeing the importance of the Temple Mount through their eyes will help you talk about how God gave it to the Jews as a signpost pointing to Yeshua, who is nearer to us than the ancient stones.

Everyone without Christ needs the good news, but that news can be especially sweet for Jews still living in hope of an established earthly kingdom. Christians can freely try to engage them in conversation and listen for significant, personal connections between their holy sites and their current spiritual condition.

Pray that God’s kingdom will be built in and through Jewish hearts, not with temporary, ancient stones but through submission to Yeshua the Messiah.

Bethany Singer lives in Jerusalem and has served among Muslim, Orthodox Christian, and Jewish people. She enjoys relating to people through local languages, music, and cuisine, and facilitating the worship of the one true God among the nations.