Years ago, when I was a young pastor, I traveled to teach at a training for evangelical pastors soon after the fall of the Soviet Union. While walking through the centers of Russia’s great cities, I was struck with horror at how many churches had been violently shut during the Communist period and converted into scientific institutes or schools. Yet Christian art was sometimes allowed to remain because of its inherent beauty. It was then that I first realized the usefulness of art in opening an avenue for the presentation of the gospel.

I visited the Hermitage Museum in Saint Petersburg and the Tretyakov Gallery in Moscow, where I found opportunities to begin gospel conversations. In the latter museum, Alexander Ivanov’s massive masterpiece, “The Appearance of Christ before the People,” continually drew crowds. Human characters in various postures of depravity confronted viewers, while John the Baptist pointed toward the approaching Christ. I was fascinated by the painting itself, which took the artist twenty years to complete, but even more by the audience’s emotional reactions.

When a Conversation about Art Leads to the Gospel

I struck up a conversation with our Russian guide and asked if she understood what the curated artwork really meant. She demonstrated a simple atheistic understanding of Russian Orthodox iconography. Alas, she did not understand the gospel behind the art. I asked her if the evil portrayed in some of the paintings required judgment. She agreed it did.

This conversation allowed me to present the good news that Jesus Christ became a human being in order to die on the cross and atone for human sin. I asked her if she believed what I was explaining. Surprisingly, she had no difficulty assenting to the deity of Christ or his incarnation, death, and resurrection. What she struggled with was her own need for personal redemption and fear of change. She admitted there was something powerful behind the art she escorted Western visitors to view.

“Architecture, music, literature, paintings, jewelry, even the clothes we wear, can be an avenue to start gospel conversations and teach basic Christian doctrines.”

It became evident to our small group that she was on the edge of receiving Christ. I pleaded with her to receive the gift of life as the other men in my group prayed. Although she hesitated to do so that day, she asked us to pray for her. She also promised she would attend the church to which we referred her. It was our last full day in the frigid city. I hope she made it to church, heard the Word in her own language, and was born again.

Visualizing Christian Doctrine

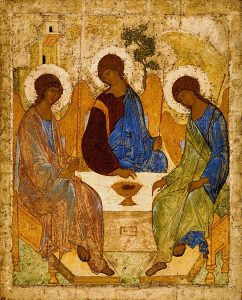

That event taught me that art can serve as an avenue for cross-cultural evangelism. But art can also be used to teach important Christian doctrines, such as the Trinity. For instance, the fifteenth-century work, “The Trinity” by Andrei Rublev, is world-renowned among theologians. On the one hand, its beauty captivates the eye through intertwining exquisite gold-leaf with brilliant blues, greens, and reds.

On the other hand, it places the three persons of the Trinity in precise positions with delicate dimensions intended to reflect what Scripture teaches about the internal divine relations of the one God who is Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. Moreover, the painting introduces both baptism and the Lord’s Supper, which Christ intended to symbolize the concrete gospel of his death and resurrection.

“The Trinity” by Andrey Rublev, (fifteenth century), in the Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow, Russia. Wikipedia Commons.

Both the Rublev and Ivanov pieces are found in Eastern Europe. When you turn to survey Western European art, especially in cities like Venice and Rome, you discover museums and churches filled with beautiful objects that can be used to explore the teachings of Scripture. You can begin with God’s ordered creation of the world in the book of Genesis and end with the final judgment of humanity by Christ in the book of Revelation. Moreover, one need not remain in European culture to find art for teaching the Christian gospel.

I have had joyous discussions in Africa regarding the profound doctrines of Scripture. For instance, a small Nigerian statue with three persons holding hands to form one community can be employed as a teaching aid for the Trinity. Interesting enough, I have found through using such art that Africans and Asians more readily embrace the doctrine of the Trinity than many in the West or Middle East.

Hyper-individualism or rigid monotheism that denies a triune God often prevents those of us in these cultures from receiving the biblical view, while other cultures often have a subtler understanding of corporate humanity, which more readily enables the teaching of the eternal God as three-and-one.

Art as an Avenue to Evangelism

One need not visit a museum to find art that can start a presentation of the saving gospel of Jesus Christ. Often, people wear art. Jewelry with religious significance like Celtic crosses are more than attractive cultural artifacts—they can prompt conversation. When you speak to a person in the United Kingdom about their own culture’s history of the gospel coming to Ireland through Patrick or to Scotland through Columba, avenues of witness immediately open.

I have been able to use not only visual art but also good English literature to share the gospel in independent bookstores. For instance, the Christian worldview behind J. R. R. Tolkien’s hugely popular Hobbit fiction series presents an immediate avenue for detailed gospel conversation.

Finally, art doesn’t even have to be Christian in order to be used as a bridge to the gospel. One sweet lady in my church in Granbury, Texas, uses tattoos she eyes upon acquaintances as a prompt for a gospel presentation. She expresses genuine interest in hearing the stories behind the art people sport on their own bodies and then turns the conversation to how the light of Christ changed her life.

Evangelicals must remember the lessons of the Reformation regarding the possibility that some art might obfuscate and detract from the preaching of the Word. But we should also remember the potential evangelistic value of the art around us. Our architecture, music, literature, paintings, jewelry, even the clothes we wear, can be an avenue to start gospel conversations and teach basic Christian doctrines. Try it. Although God himself can never be fully captured by human art, he may sovereignly decide to work through it, together with your voice, to draw people to Christ.

Dr. Malcolm B. Yarnell is a research professor at Southwestern Baptist Theological Seminary and a teaching pastor at Lakeside Baptist Church. He is the author of God the Trinity: Biblical Portraits. You can find him on Twitter.